University of Texas at Austin astronomer Steven Finkelstein has led a team that has discovered and measured the distance to the most distant galaxy ever found. The galaxy is seen as it was at a time just 700 million years after the Big Bang.

Although observations with NASA's Hubble Space Telescope have identified many other candidates for galaxies in the early universe, including some that might perhaps be even more distant, this galaxy is the farthest and earliest whose distance can be definitively confirmed with follow-up observations from the Keck I telescope, one of a pair of the world's largest Earth-bound telescopes.

The result are published in the Oct. 24 issue of the journal Nature.

"We want to study very distant galaxies to learn how galaxies change with time, which helps us understand how the Milky Way came to be," Finkelstein said.

That's what makes this confirmed galaxy distance so exciting, because "we get a glimpse of conditions when the universe was only about 5 percent of its current age of 13.8 billion years," said Casey Papovich of Texas A&M University, second author of the study.

Astronomers can study how galaxies evolve because light travels at a certain speed, about 186,000 miles per second. Thus, when we look at distant objects, we see them as they appeared in the past. The more distant astronomers can push their observations, the farther into the past they can see.

The devil is in the details, however, when it comes to making conclusions about galaxy evolution, Finkelstein points out. "Before you can make strong conclusions about how galaxies evolved, you've got to be sure you're looking at the right galaxies."

The devil is in the details, however, when it comes to making conclusions about galaxy evolution, Finkelstein points out. "Before you can make strong conclusions about how galaxies evolved, you've got to be sure you're looking at the right galaxies."

This means that astronomers must employ the most rigorous methods to measure the distance to these galaxies, to understand at what epoch of the universe they are seen.

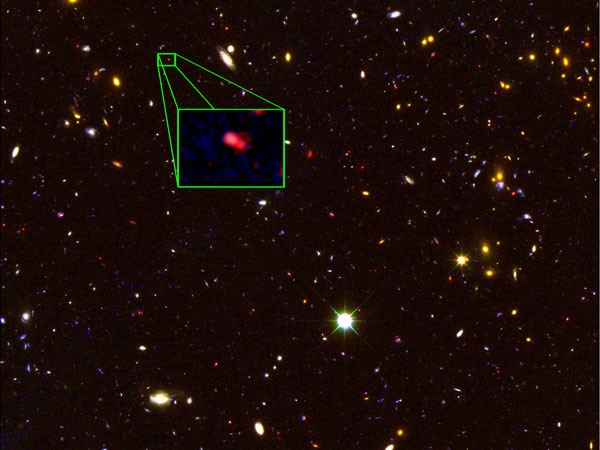

Finkelstein's team selected this galaxy, and dozens of others, for follow-up from the approximately 100,000 galaxies discovered in the Hubble Cosmic Assembly Near-infrared Deep Extragalactic Legacy Survey (CANDELS), of which Finkelstein is a team member. The largest project in the history of Hubble, CANDELS used more than one month of Hubble observing time.

The team looked for CANDELS galaxies that might be extremely distant, based on their colors from the Hubble images. This method is good but not foolproof, Finkelstein said. Using colors to sort galaxies is tricky because closer objects can masquerade as distant galaxies.

So to measure the distance to these potentially early-universe galaxies in a definitive way, astronomers use spectroscopy — specifically, looking at how much a galaxy's light wavelengths have shifted toward the red end of the spectrum during their travels from the galaxy to Earth because of the expansion of the universe. This phenomenon is called "redshift."

The team used Keck Observatory's Keck I telescope in Hawaii, one of the largest optical/infrared telescopes in the world, to measure the redshift of the CANDELS galaxy designated z8_GND_5296 at 7.51, the highest galaxy redshift ever confirmed. The redshift means this galaxy hails from a time only 700 million years after the Big Bang.

Read more about this discovery in the Department of Astronomy news release.

Comments