Researchers at the University of Texas at Austin have for the first time revealed how a group of drugs that are being developed to treat hepatitis C works. Pharmaceutical companies might be able to apply these new insights to future drugs designed to address a deadly disease.

The hepatitis C virus attacks the liver, which over time can lead to fibrosis, cirrhosis or cancer. According to a study released last week by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), more Americans died from complications of hepatitis C in recent years than from 60 other infectious diseases combined, including HIV, pneumococcal disease and tuberculosis. Between 3.5 and 7 million people worldwide have chronic hepatitis C.

In 2013, the FDA approved a new drug to treat hepatitis C, sofosbuvir (sold as Solvadi). When combined with another drug, each targeting a different part of the mechanism that the virus uses to replicate, the treatment is 100 percent effective at wiping out the virus. Other highly effective drug cocktails aimed at hepatitis C have since come on the market.

"Manufacturers combine drugs that attack different targets in order to prevent the virus from evolving resistance," says Kenneth Johnson, professor of molecular biosciences. "That's why we still need to find more drugs that target new sites on the virus to block replication."

Pharmaceutical companies have been studying a new group of drugs called NNI2's (non-nucleoside inhibitors binding to thumb site 2) that block viral replication by targeting a different function of the cellular machinery than those targeted by other drugs. Until now, scientists didn't understand how NNI2's work.

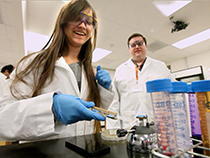

Johnson and graduate student Jiawen Li discovered what's happening.

To live and multiply, the hepatitis C virus has to replicate its genetic code stored in strands of RNA. It uses a special copying machine, or protein, that looks a bit like a hand.

Here's how it makes copies: The hand folds around a single strand of RNA and uses its thumb to hold it in place. Then the hand starts to add the building blocks of a second strand, like beads on a necklace, alongside the first. The original strand of RNA acts both as a scaffold and a template. As the double-stranded RNA grows, the hand opens up to allow it to emerge and continue growing to its full length. Eventually, there are two complete strands where before there was just one.

Johnson and Li found that NNI2's bind to the back of the thumb and prevent the hand from opening up, thus inhibiting RNA replication. By making the thumb rigid, the inhibitor effectively freezes the hand in the closed state.

"Many people working toward drug discovery treat a protein as a rigid structure and try to find inhibitors to dock with it," says Johnson. "But proteins are very dynamic. They undergo large changes in structure. These inhibitors work because they stop the protein from changing shape."

The results appeared May 6th in The Journal of Biological Chemistry in an article titled, "Thumb Site 2 Inhibitors of Hepatitis C Viral RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase Allosterically Block the Transition from Initiation to Elongation."

The high cost of these new lifesaving drugs ($84,000 for a full course of treatment of Solvadi) has led many insurers to limit coverage to the sickest patients, which has been controversial. New York State recently won a lawsuit forcing insurance companies to fully cover the drugs, and the federal government has said that Medicaid cannot set limits on who receives them.

Johnson says for these new insights to be developed into an alternative treatment, they will first have to "spark the interest in the pharmaceutical companies to realize that our discoveries highlight another avenue of research to derive another effective drug."

Comments 1

The increasing death rate of hepatitis C patients must have something to do with the lifestyle, as well as the changing environment. I do think that the last one is the main factor, which contributes a lot to this aspect. In this aspect, drug discovery plays a very important role. We do hope scientists can achieve more in the future.