In May of 1973, two physicists from The University of Texas at Austin went to the desert of Mauritania to set up an observatory in advance of the June 30 solar eclipse.

A month later, with a team from the university, they looked up at the stars visible during the eclipse, and helped prove Albert Einstein right.

A month later, with a team from the university, they looked up at the stars visible during the eclipse, and helped prove Albert Einstein right.

Einstein had predicted that light passing through a gravitational field would be deflected more than was accounted for by Newtonian physics, and it was a 1919 observation of that effect, by British physicist Arthur Eddington, that had made Einstein famous.

Until 1973, however, when Cecile Dewitt-Morette and her husband, Bryce Dewitt, went to the desert, no one had backed up Einstein with the tools and precision of modern astronomy.

“Historically speaking, the 1919 plates were significant, because they created the fame of Einstein,” says Dewitt-Morette, professor emerita of physics. “Scientifically speaking, however, they were not convincing. They got the right theoretical values, but they were lucky.” By comparing the eclipse measurements to those taken at night by a second expedition, six months later, when the starlight wasn’t being curved by the sun, Dewitt-Morette and her colleagues were able to confirm Einstein’s relativistic prediction with far greater precision. It was a landmark moment in physics. It was also the result of some very down-to-earth hard work.

By comparing the eclipse measurements to those taken at night by a second expedition, six months later, when the starlight wasn’t being curved by the sun, Dewitt-Morette and her colleagues were able to confirm Einstein’s relativistic prediction with far greater precision. It was a landmark moment in physics. It was also the result of some very down-to-earth hard work.

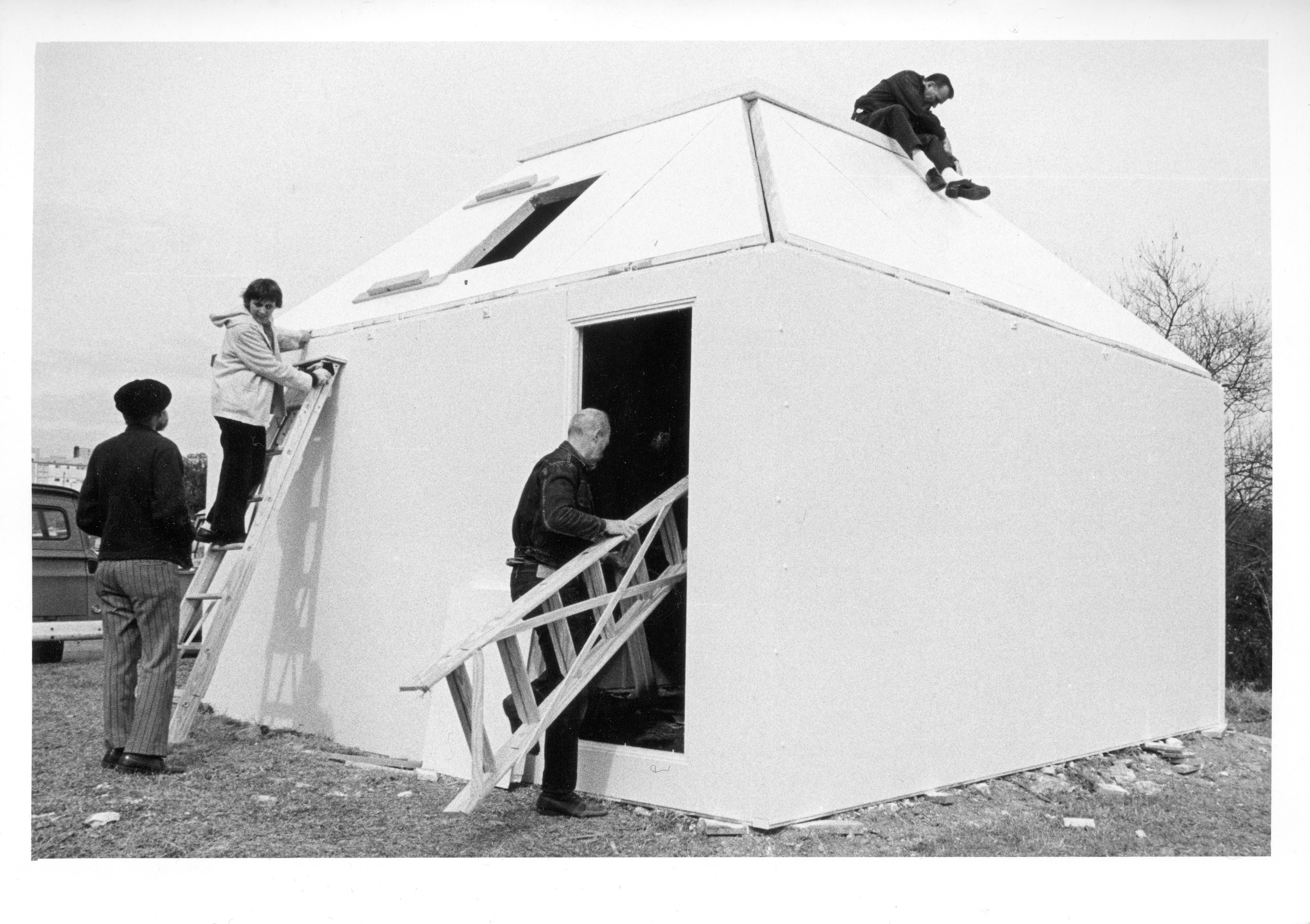

“I was on the roof of the observatory we had built, holding a piece of cardboard as a shutter,” says Dewitt-Morette. “When Bryce would say, ‘Close shutter,’ I would, and when he would say, ‘Open shutter,’ I would. For those seven minutes, I obeyed him without any question.”

Comments