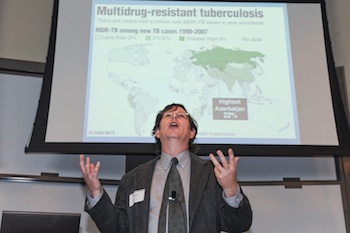

Andy Ellington discusses how point-of-care diagnostics may revolutionize health care.

Biochemist Andy Ellington discussing the potential significance of point-of-care diagnosticWith nearly half a million new cases diagnosed every year, multi-drug-resistant tuberculosis is a major worldwide health concern. The disease is especially prevalent in areas where medical care is sparse and it can take weeks to get back test results. The long turnaround time makes it difficult to monitor the spread of the epidemic and delays treatment for patients facing life-or-death situations.

Biochemist Andy Ellington discussing the potential significance of point-of-care diagnosticWith nearly half a million new cases diagnosed every year, multi-drug-resistant tuberculosis is a major worldwide health concern. The disease is especially prevalent in areas where medical care is sparse and it can take weeks to get back test results. The long turnaround time makes it difficult to monitor the spread of the epidemic and delays treatment for patients facing life-or-death situations.

A solution may be on the way.

Scientists are developing new tools to detect the presence of drug-resistant tuberculosis and other diseases rapidly and inexpensively. Andrew Ellington, a professor of chemistry and biochemistry at The University of Texas at Austin, presented findings from his research May 3 as part of the Texas Enterprise Speaker Series.

Using DNA analysis, Ellington and his colleagues are studying new types of tests called point-of-care diagnostics, which could make it easier for patients to diagnose their own health problems even when the nearest hospital is miles away. Similar processes are already used to quickly test for pregnancy, steroid use and strep throat, but the technology has not yet been widely adopted for other uses due to various technical, economic and social hurdles. For example, current tests for drug-resistant tuberculosis are not nearly sensitive enough, which often allows the disease to go undetected.

Ellington believes that will soon change. Researchers are creating increasingly reliable tests that can be distributed to remote locations around the world. Testing for tuberculosis could be as simple as folding a slip of paper, waiting for it to change color, and posting a photograph of the strip online.

When that breakthrough comes, point-of-care technology could ultimately push health care in a new direction that gives patients more oversight of their own medical decisions, he said.

“My dream is that people will take control of their own health care,” Ellington said.

Improving Access

In the same way that customer support centers help people solve computer problems remotely, new point-of-care tests would allow people to diagnose health problems without having to leave home— making it easier and more convenient for patients to get the help they need.

“What if there were a variety of tests for a variety of conditions and you uploaded the results of your tests? You could interface with your physician all you want, ask clinicians all you want, and have health care providers help you out,” Ellington said. “What if we could just log on to get our health care?”

Power to the Patients

Point-of-care technology also gives patients valuable guidance in making decisions on their own, Ellington said. For instance, if there were a daily test that showed the impact of treatment in real time — and how it is making a difference — patients might take a more active interest in keeping up with a recovery regimen.

Ellington said future point-of-care tests could provide patients with more options and, to some extent, allow them act as their own physicians. Rather than bringing children into see a doctor with every case of the sniffles, for instance, parents could do a preliminary check on their own at home. Home tests could also ease the burden on the country’s strained health care system, he said, eliminating some routine doctor visits.

The home pregnancy test kit is a historic example of how patient-controlled tests provide not only convenience but also a measure of social empowerment, according to Ellington. The kits were first developed in the mid-1970s, offering women more independence in overseeing their personal health matters.

“At the time the pregnancy test kit was developed, there was a social revolution going on in parallel with the scientific one,” Ellington said.

He acknowledges that it’s unclear whether Americans will be comfortable with the idea of diagnosing themselves, without a doctor’s office visit. But, he said, these basic tests aren’t meant as substitutes for physicians or clinics; rather, they give patients access to information they wouldn’t otherwise have.

“If people are ready to take control of their own health care, we’re ready to provide them with the technology to do so,” Ellington said.

Technical, Economic or Social Problem?

Even if people are ready to take more responsibility for their own health care, paying the costs associated with the transition is another issue altogether. From the consumer’s perspective, not everyone has reliable access to computers to upload self-test results and manage online health management programs. There are also costs on the provider’s side, including producing the tests and the systems for analyzing them.

While the expense factor may be hindering the widespread adoption of point-of-care diagnostics for now, Ellington argues that costs will come down over time. Until then, it may be necessary to offer financial incentives to help self-testing gain a foothold.

“I’m a great believer in Adam Smith and the invisible hand of capitalism, but I think somehow we need to incentivize individuals,” Ellington said. “We have to figure out some way economically to do this.”

But Reuben McDaniel, the Charles and Elizabeth Prothro Regents Chair in Health Care Management at McCombs, offered an alternative view in a discussion following Ellington’s presentation. He suggested that economic incentives could actually be a bad investment, because Americans often make decisions according their own beliefs or social norms rather than taking the time to evaluate how their own well-being might be affected.

“I believe that a significant part of the issue of moving our health care to some new form is really a social problem instead of a technical problem,” he said, noting that economic incentives might not provide enough motivation for many people to change their established behaviors — such as consulting a doctor at the first sign of a cold.

But Ellington believes that it is possible to convince people that there are real advantages to revamping the system — namely, making health care simpler, cheaper, and more accessible for everyone.

“There needs to be re-education about what value is,” Ellington said.

By Rob Heidrick, Texas Enterprise

Comments