Inspired by the paper-folding art of origami, chemists at have developed a 3-D paper sensor that may be able to test for diseases such as malaria and HIV.

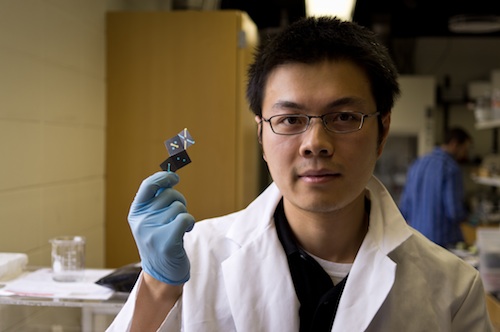

Graduate student Hong Liu was inspired to develop the sensor after recalling the origami lessons he got as a schoolboy growing up in China. Photo by Alex Wang.

Graduate student Hong Liu was inspired to develop the sensor after recalling the origami lessons he got as a schoolboy growing up in China. Photo by Alex Wang.

AUSTIN, Texas - Inspired by the paper-folding art of origami, chemists at The University of Texas at Austin have developed a 3-D paper sensor that may be able to test for diseases such as malaria and HIV for less than 10 cents a pop.

Such low-cost, “point-of-care” sensors could be incredibly useful in the developing world, where the resources often don’t exist to pay for lab-based tests, and where, even if the money is available, the infrastructure often doesn’t exist to transport biological samples to the lab.

“This is about medicine for everybody,” says Richard Crooks, the Robert A. Welch Professor of Chemistry.

One-dimensional paper sensors, such as those used in pregnancy tests, are already common but have limitations. The folded, 3-D sensors, developed by Crooks and doctoral student Hong Liu, can test for more substances in a smaller surface area and provide results for more complex tests.

“Anybody can fold them up,” says Crooks. “You don’t need a specialist, so you could easily imagine an NGO with some volunteers folding these things up and passing them out. They’re easy to produce, so the production could be shifted to the clientele as well. They don’t need to be made in the developed world.”

The results of the team’s experiments with the origami Paper Analytical Device, or oPAD, were published in October in the Journal of the American Chemical Society and last week in Analytical Chemistry.

The inspiration for the sensor came when Liu read a pioneering paper by Harvard University chemist George Whitesides.

Whitesides was the first to build a three-dimensional “microfluidic” paper sensor that could test for biological targets. His sensor, however, was expensive and time-consuming to make, and was constructed in a way that limited its uses.

“They had to pattern several pieces of paper using photolithography, cut them with lasers, and then tape them together with two-sided tape,” says Liu, a member of Crooks’ lab. “When I read the paper, I remembered when I was a child growing up in China, and our teacher taught us origami. I realized it didn’t have to be so difficult. It can be very easy. Just fold the paper, and then apply pressure.”

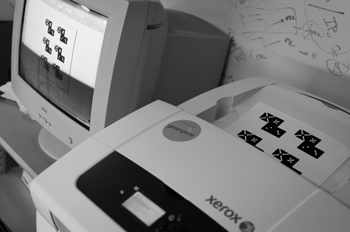

The origami Paper Analytical Device (oPAD) can be printed on a common office printer. Photo by Alex Wang.Within a few weeks of experiments, Liu had fabricated the sensor on one simple sheet using photolithography or simply an office printer they have in the lab. Folding it over into multiple layers takes less than a minute and requires no tools or special alignment techniques. Just fingers.

The origami Paper Analytical Device (oPAD) can be printed on a common office printer. Photo by Alex Wang.Within a few weeks of experiments, Liu had fabricated the sensor on one simple sheet using photolithography or simply an office printer they have in the lab. Folding it over into multiple layers takes less than a minute and requires no tools or special alignment techniques. Just fingers.

Crooks says that the principles underlying the sensor, which they’ve successfully tested on glucose and a common protein, are related to the home pregnancy test. A hydrophobic material, such as wax or photoresist, is laid down into tiny canyons on chromatography paper. It channels the sample that’s being tested — urine, blood, or saliva, for instance — to spots on the paper where test reagents have been embedded.

If the sample has whatever targets the sensor is designed to detect, it’ll react in an easily detectable manner. It might turn a specific color, for instance, or fluoresce under a UV light. Then it can be read by eye.

“Biomarkers for all kinds of diseases already exist,” says Crooks. “Basically you spot-test reagents for these markers on these paper fluidics. They’re entrapped there. Then you introduce your sample. At the end you unfold this piece of paper, and if it’s one color, you’ve got a problem, and if not, then you’re probably OK.”

Crooks and Liu have also engineered a way to add a simple battery to their sensor so that it can run tests that require power. Their prototype uses aluminum foil and looks for glucose in urine. Crooks estimates that including such a battery would add only a few cents to the cost of producing the sensor.

“You just pee on it and it lights up,” says Crooks. “The urine has enough salt that it activates the battery. It acts as the electrolyte for the battery.”

For more information, contact: Daniel Oppenheimer, College of Natural Sciences, 512 745 3353.

Comments