Most modern computers and communications devices use electrons to transmit and process information. But when they're crammed onto smaller and smaller devices, electrons become unruly, generating a lot of heat. Scientists have long dreamed of replacing electrons with particles of light called photons. Because photons don't generate much heat and move at light speed, computer chips could theoretically be made much smaller and faster than current chips.

But photons can be finicky too: for example, they don't like to make sharp turns. When confronted with a bent path, they tend instead to reflect or scatter. Moreover, if they're too close together, any two streams of photons suffer from a kind of interference called cross talk. Earlier this year, a team of researchers from The University of Texas at Austin announced the design of a device—called a photonic topological insulator (PTI)—that can bend the path of light by 120 degrees without any reflections.

"For a long time people thought this reflection problem was almost like a physical law that you cannot break," says Tzuhsuan Ma, a physics PhD student who designed the new device while working with professor Gennady Shvets. "That's the most exciting part to me. Now we have this device and have shown that you can bend light without it reflecting."

In addition to providing a key component in photonic computers, the device could also enable more compact antennas for cell phone transmitters and receivers.

The new device was inspired by materials discovered over a decade ago that allow electrons to travel along the outer edges without being deflected, even when encountering folds, bumps and impurities. There was no guarantee that an analogous device could be built for photons.

After several of Ma's earlier designs failed, he decided to take a break from directly working on the problem for a few months and study up on the fundamentals of topological photonics. When he came back to the problem, it only took a couple of weeks to hit upon what became a successful design. He says it taught him a valuable lesson about doing science.

"If you're stuck on something, don't just try to do the hard-core thinking," he says. "Slow down. Do something else. Then come back to it."

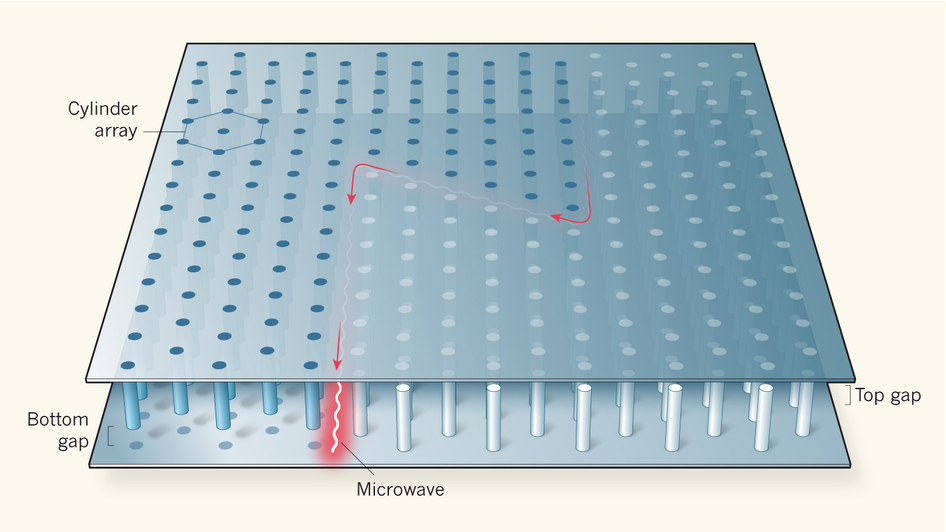

The design, described in the journal Physical Review Letters in March, was tested on a computer model that is thought to precisely represent the way that light interacts with matter. It's called a first principles model, meaning that it uses Maxwell's equations without approximations that would speed up calculations, but risk missing important physical effects. The team has now constructed a full-size PTI that looks like a metallic ice cream sandwich two meters long and one meter wide. The researchers are testing it to confirm that they really can bend light sharply as predicted.

But don’t be fooled by the large size of this experimental setup. The researchers believe the concept will easily scale down to much smaller devices operating at a wide range of frequencies.

The work was also highlighted in a News & Views article in the journal Nature in June.

In addition to Ma and Shvets, the research team included Alexander Khanikaev, a former postdoctoral researcher and now an assistant professor at the City University of New York, and Hossein Mousavi, a postdoctoral researcher in the Cockrell School of Engineering.

Comments