Two researchers at the Texas Natural Science Center are combining art and science in a unique form that highlights a beauty in dead animals and animal biodiversity in Texas.

When Adam Cohen (Biology '01) and Ben Labay (Biology '02) are not at work in the preserved specimen collection at the science center, the two scientists spend their spare time collaborating on a project known as Inked Animal.

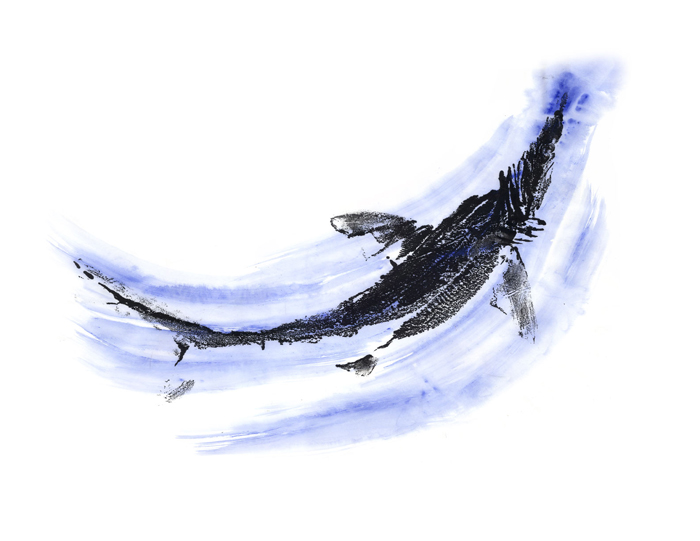

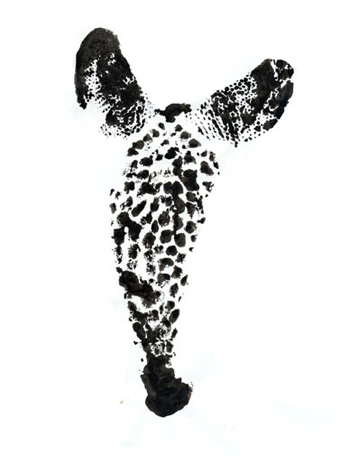

The duo create artistic impressions of dead animals. Ordinarily these animals would slowly decay – in many cases they already have – and eventually be forgotten, but Inked Animal creates a lasting impression that celebrates the beauty of the natural world. Some pieces bring a face to things that go bump in the night, depicting nocturnal creatures that the average person would never meet. Other pieces bring the subject to life, the animal nearly leaping off the page.

Here we present a sampling of artwork from Inked Animal, interspersed with a series of questions and answers provided by Adam and Ben.

What is Inked Animal all about?

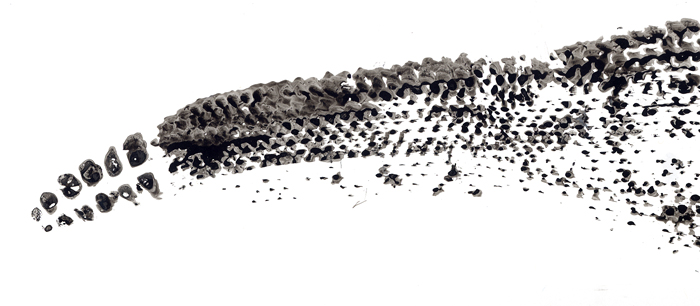

Inked Animal is a project centered on creating lasting impressions of animals, each representing the reality of the original specimen. On one level they are simply realistic documentations of the specimens that preserve the animal forever (as a museum specimen would), but we also see these prints as crossing a blurry line into art in that they provoke people to appreciate the unique and sometimes haunting beauty of the animals. Many of our prints are of partially dissected animals and capture unusual positions or body parts. We experiment constantly with materials and how to use them to create interesting effects and our project might better be called the Inked Animal Laboratory. We work mostly in Texas and as a body of work our prints also serve to illustrate the biodiversity of our state.

How did this project start and how has it evolved?

We are both full-time fish biologists with backgrounds in art. So the project emerged naturally as a diversion from working all day long in science. We started very informally printing fishes (Gyotaku) and quickly realized there was great potential to expand. We just started exploring processes and materials and our first prints weren't at all fit to show, but we were encouraged by what was being produced and quickly we developed some unique methods that produced satisfying results. It helps that we work together because we keep each other inspired, which keeps the "experiment" constantly alive.

How does Gyotaku relate to your work?

Gyotaku has its roots in science to a certain extent in that it was developed in Japan as a means to document the size and type of fish that fishermen were catching. It also shows up in scientists' field notes as a way of documenting a specimen without depositing the actual animal in a museum. So it really started as a practical documentation tool that only later developed into an intricate art form.

We really like working with fish, which is how Gyotaku traditionally has been done, but after experimenting with printing other kinds of animals we're becoming less interested in fish and have come to see the art form in a much broader light. We really like the fact that the paper actually touches the animal and its DNA is included as part of the art - many pieces have blood, guts, feces or fur that are a visible part of the art. At first we sought to print intact animals in a very pristine way, as in the tradition of Gyotaku. Now we are starting to realize that some of the damaged specimens – mummified, rotten, or dismembered - make the most interesting prints and tell more interesting stories. Our tolerance for "gross" is very high.

As scientists, could you talk about the scientific part of Inked Animal?

We work together in the preserved specimen collections of the Texas Natural Science Center where Adam is the ichthyology collections manager and Ben does data analyses and data modeling. We both do a lot of fieldwork collecting fish and other animals for the museum and spend most of our time in more of a science mode. I think our science training has imparted to us an attention to details of anatomy which shows up in the art. Our knowledge of Texas natural history has generated a much deeper appreciation and respect for our subject material and as a practical matter helps us find animals we'd like to print.

How does being a scientist change the way your art is completed, researched, and created?

Our methods have been developed through a lot of experimentation and testing of ideas, most of which don't pan out. I wouldn't go so far as to say that we use the scientific method in our art process, but it is an ad hoc sort of experimental process. As biologists, we start from a place of curiosity, reverence and appreciation with regards to the animals and we think that comes through in the final pieces. We also bring some familiarity to certain taxa, so are able to accentuate diagnostic traits in the process of printing.

What do you hope the public will take away from Inked Animal?

We hope people leave feeling they saw something very special that they couldn't see anywhere else. It's been interesting to us to see how people respond. Sometimes people look very closely at a hair or blood stain and they realize that the animal was in fact right there touching paper – it can be a bit of a shock. Often people think the animal impressions look very much alive, and imagine that somehow we created the prints from actual live animals – that would be impossible! We've been told that some prints look "cute," but many of the prints were created from animals that were disfigured, long dead and putrefied – not cute for sure. It often surprises us how the prints feel very different than the dead animal in the flesh.

Do you do any outreach to kids or the general public?

We work with kids in summer camp and workshops, showing them how to print natural objects. They love being able to learn about the animals, handle them and take art home. We'd like to do more of that. We'd like for the public to look closely at our art and notice details in the animals that they might not have otherwise noticed. Some of these animals are shy or nocturnal and the prints can allow people to experience those animals that they might not have opportunity to see alive. We added natural history information to our website which adds an educational component. We hope that our efforts inspire people to take more of an interest in Texas natural history, and the natural environment.

How are the prints created?

We are constantly experimenting with our methods. Typically, we apply ink or paint to an animal and then press papers of varying thicknesses against it to produce images. Recently we started using thinned, watery clay instead of ink or paint, which we think results in a more earthy feel appropriate for the subject material. After we get an impression we do some additional painting with a brush or our fingers to add color, which gives it depth and highlights. But we try to keep the raw feel of the print which includes elements of the process such as splatter marks and drips.

For more information, contact: Adam Cohen and Ben Labay, adamespeleecohen@gmail.com and benlabay@gmail.com, www.inkedanimal.com; Inked Animal's work is represented by Art.Science.Gallery. of Austin; Steve Franklin, College of Natural Sciences Communications, sefranklin@mail.utexas.edu, (512) 232-3692

Comments