When considering college students and their drinking patterns through college, not everyone is the same, says Dr. Kim Fromme, Professor of Clinical Psychology and member of the Waggoner Center for Alcohol and Addiction Research.

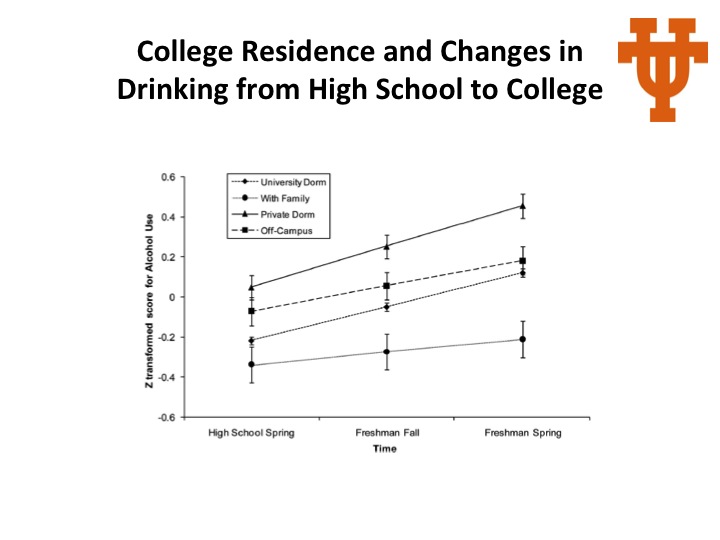

By Samuel Thompson (originally published in Catalyst, the newsletter of the Natural Sciences Council) Fromme's study revealed that the residence selected in students' first years of college was associated with different rates of alcohol consumption: commuting students living at home being the lightest drinkers, followed by campus dorms, off campus apartments, and finally private dorms being the heaviest drinkers. Fromme K, Corbin WR, Kruse MI. "Behavioral risks during the transition from high school to college." Developmental Psychology. 2008;44:1497–1504.

Fromme's study revealed that the residence selected in students' first years of college was associated with different rates of alcohol consumption: commuting students living at home being the lightest drinkers, followed by campus dorms, off campus apartments, and finally private dorms being the heaviest drinkers. Fromme K, Corbin WR, Kruse MI. "Behavioral risks during the transition from high school to college." Developmental Psychology. 2008;44:1497–1504.

When considering college students and their drinking patterns through college, not everyone is the same, says Dr. Kim Fromme, Professor of Clinical Psychology and member of the Waggoner Center for Alcohol and Addiction Research.

Dr. Fromme conducted a 6 year longitudinal study on first-time incoming U.T. students from their senior year of high school through their college years, mapping along the way peer, parent, and individual aspects that influence drinking habits. The students completed online surveys about their senior year of high school, for each fall and spring semester of years 1-3 at U.T., and in the fall semester of years 4-6. The students also recorded 30 days of daily monitoring each year for 4 years. Alcohol use (quantity, frequency, and binge episodes), and how drunk one “feels” (subjective intoxication) was measured.

After the completion of the study, Dr. Fromme has some interesting findings.

Usually, if the students were heavier drinkers in high school, it meant that they usually would select into a heavier drinking peer groups. In the alcohol and addiction research world, this process of choosing a like-minded social group is known as selection, quickly followed by another related process called socialization, in which students adapt and match the amounts their friends drink. In addition to their peers, the parenting style and personality also influenced student’s drinking, with a closer relationship and monitoring by the parents associated with a lower alcohol use, and a personality type that was prone to taking risks associated with a higher alcohol use.

The study also revealed that the residence selected in their first years of college was also associated with different rates of alcohol consumption: commuting students living at home being the lightest drinkers, followed by campus dorms, off campus apartments, and finally private dorms being the heaviest drinkers. (Fromme, Corbin, & Kruse, 2008)

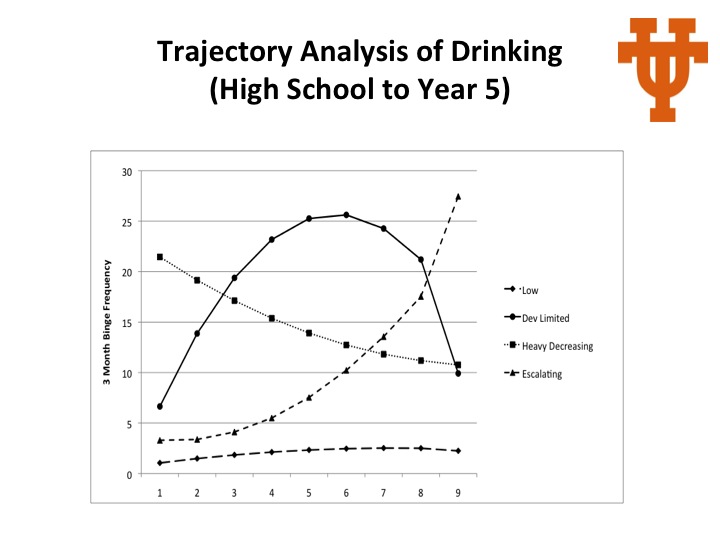

Dr. Fromme found that students fell into four categories based on their change in alcohol use at U.T. Image property of Kim Fromme, The University of Texas at Austin.Interestingly, Dr. Fromme found that students fell into four categories based on their change in alcohol use at U.T. The lightest drinkers in high school seemed to stay relatively light throughout their 4 years, while the heaviest drinkers in high school decreased their intake over the time they were at U.T. According to the focus groups conducted by Dr. Fromme, this group felt that they had “done all of their partying in high school.”. Another group of relatively light drinkers in high school seemed to dramatically increase their drinking rate in their first two years, from what may be due to the lack of parental oversight, but drinking tapered off once they reached their junior year, due to what Dr. Fromme speculates as academic pressures in the form of not getting a job or into graduate school after college due to poor achievement. The most disturbing group began as light drinkers in high school but whose drinking became heavier and heavier as they proceeded through the study. It is suspected that the escalating category is due to a decreased response to alcohol, with the individuals drinking more and more to get the same effect.

Dr. Fromme found that students fell into four categories based on their change in alcohol use at U.T. Image property of Kim Fromme, The University of Texas at Austin.Interestingly, Dr. Fromme found that students fell into four categories based on their change in alcohol use at U.T. The lightest drinkers in high school seemed to stay relatively light throughout their 4 years, while the heaviest drinkers in high school decreased their intake over the time they were at U.T. According to the focus groups conducted by Dr. Fromme, this group felt that they had “done all of their partying in high school.”. Another group of relatively light drinkers in high school seemed to dramatically increase their drinking rate in their first two years, from what may be due to the lack of parental oversight, but drinking tapered off once they reached their junior year, due to what Dr. Fromme speculates as academic pressures in the form of not getting a job or into graduate school after college due to poor achievement. The most disturbing group began as light drinkers in high school but whose drinking became heavier and heavier as they proceeded through the study. It is suspected that the escalating category is due to a decreased response to alcohol, with the individuals drinking more and more to get the same effect.

While the amount that the students drank is an important component in the study, Dr. Fromme is also interested in the behaviors that may be influenced by alcohol, such as risk taking and drunk driving.

“…We all know that people can do stupid things when they’re drunk than when they’re sober. And I’m sure you can all think of examples of people who have regretted some form of behavior when they’ve been drinking,” Dr. Fromme says.

But how does drinking influence risky behaviors? Turns out there are several theories.

“Alcohol Myopia… [which] goes by the name of the Attention allocation Model. It shows that alcohol serves to reduce your cognitive processing capacity so that you are less able to attend to and process cues in your environment,” says Dr. Fromme, “[So] you’re more likely to be reactive in the example of provocation.”

In addition, Dr. Fromme has done a series of studies in her “Bar Lab” on the second floor of the Seay building that has shown that alcohol reduces the perception of risk to the user. No detection of risk means the user is more likely to do risky things.

“And I’m going to propose subjective intoxication as another means by which people get in trouble with drinking,” says Dr. Fromme, “so the question is: is it how drunk you feel versus how drunk you really are that might get you into trouble with some of these behaviors.”

And the study supported her ideas: heavier drinkers were more likely to exhibit increased risk of aggression, although this did not necessarily mean more incidences of drinking and driving. Men usually had higher incidences than women in both categories. Also, curiously enough, low levels of subjective intoxication (where one feels “fine” but is actually intoxicated) led to higher rates of drinking and driving, and higher levels of subjective intoxication led to more aggressive behaviors. “Probably not a good idea to use your own judgment about how drunk you are to decide whether or not you’re ok to drive,” says Dr. Fromme.

What’s next on the agenda for Dr. Fromme? She hopes to have a sequel to this study, and she thanks the Texas taxpayers and the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism for funding the study.

Comments