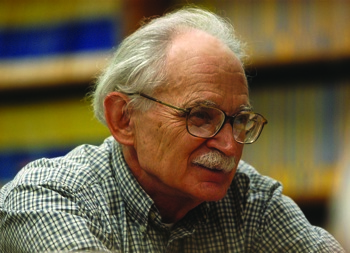

Curiosity may be the most powerful scientific tool, but hard work runs a close second. So says Dr. Allen Bard, who has used both to great effect in a scientific career that has spanned nearly half a century so far.

During that time, Bard has amassed an impressive list of discoveries, publications and scientific awards. Among the highlights, he co-discovered electrogenerated chemiluminescence, the emission of light when molecules exchange electrons, which today serves as the basis for highly sensitive immunoassays. He also developed the scanning electrochemical microscope, used to observe chemical reactions between handfuls of atoms. And his electrochemical research has contributed to pollution remediation, semiconductor design and solar power.

During that time, Bard has amassed an impressive list of discoveries, publications and scientific awards. Among the highlights, he co-discovered electrogenerated chemiluminescence, the emission of light when molecules exchange electrons, which today serves as the basis for highly sensitive immunoassays. He also developed the scanning electrochemical microscope, used to observe chemical reactions between handfuls of atoms. And his electrochemical research has contributed to pollution remediation, semiconductor design and solar power.

But when discussing his achievements, Bard prefers to focus on a different aspect of his work.

“If you want to know the most important thing I’ve done, it’s train students and postdocs,” Bard said. Regarding his research, he said, “Whatever I tell you is important now is not going to seem as important in 10 years, but the students will be. That’s really it.”

As the Norman Hackerman-Welch Regents Chair in Chemistry and director of the Center of Electrochemistry, Bard leads a team of graduate students and postdoctoral fellows investigating processes in electroorganic chemistry, photoelectrochemistry and other fields.

His team has led the development of these fields in recent years, with Bard guiding junior colleagues along the often-difficult road to discovery.

“As I tell my students, most of the time research is not going well,” Bard says. “That’s the real truth. There are a hundred ways things can go wrong–machines break, chemicals are impure–and so you just keep fighting. In other words, nature gives up its information, but not very willingly.”

After receiving his bachelor’s from the City College of New York and a doctorate in chemistry from Harvard University, he came to The University of Texas at Austin in 1958 to pursue electrochemical research.

[pullquote]Science is about the drive to understand, to push the frontier...[/pullquote]“Science is about the drive to understand, to push the frontier,” Bard says. “Sometimes you can see an application, but a lot of times you can’t.”

While fundamental research doesn’t always have clear applications at first, he adds, history shows that it often pays off handsomely. Such was the case with electrogenerated chemiluminescence, which dramatically improved the sensitivity of immunoassays, a ubiquitous test used for developing new pharmaceutical drugs, testing for the presence of AIDS and other diseases, identifying environmental toxins and for other purposes.

“We just wanted to know the details of how electrons transfer among molecules,” Bard says. “It was interesting to see this new phenomenon. It was only after 20 years that we saw a possible application and developed it. And that has happened continually throughout my career.”

Looking forward, Bard sees some of the most interesting problems at the interface between chemistry and biology.

“Biological systems are basically chemical systems,” he says. “They are exceedingly complicated chemical systems, but they are chemical systems and can be interpreted purely as such.”

He also sees significant work ahead in energy research, particularly converting solar energy into electricity efficiently, and in analytical chemistry, where scientists would like to find techniques to analyze individual molecules.

Investigating these areas may lead to more awards for Bard, a member of the National Academy of Sciences and recent recipient of the 2004 Welch Award in Chemistry in recognition of his lifelong achievements. Regardless, he will likely accept them with modesty.

“Awards are nice,” Bard says. “But I always tell my students you only go through two stages in your career – when you are underappreciated and when you are overappreciated.”

“The most important thing is to work hard. That’s really it,” he says.

By Tom Gerrow

This article appeared originally in Focus on Science magazine in Fall 2004.

Comments